Known as one of Austria’s most famous painters, and renowned as an important founder of

the Vienna Secession in 1897, Gustav Klimt remains a significant figure in art history. Pieces

including The Kiss (1908 – 09) and Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) are often celebrated as his

best, and Klimt continues to be admired and revered throughout the art world.

Having trained at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (the Kunstgewerbeschule), where he

learned from the study of Old Masters such as Rubens and Velázquez, Klimt was

accomplished as a painter and drawer, and his murals, sketches, and paintings continue to

be celebrated. Although Klimt is arguably best known for his ‘Golden Phase’, when he began

to integrate gold leaf into his pieces, other artworks like Fish Blood (Blood of Fish) are

nonetheless important for what they reveal about Klimt’s changing practice, and his

departure from more conventional Realist aesthetics and techniques.

Historical Background to Fischblut (Blood of Fish)

Klimt continues to be recognised for his radical focus on the sensuality and eroticism of the

female body. However, at the time of his work, the degree to which Klimt took inspiration

from the female body led to criticism.

In 1894, Klimt had been commissioned to produce three ceiling paintings for the Great Hall

of the University of Vienna. Upon their creation, these paintings – Philosophy, Medicine, and

Jurisprudence – were criticised for what was seen as their pornographic aesthetics. Klimt

was so enraged by this response and refusal of his art that it prompted him to swear off

public commissions forever. The paintings he created were never hung at the University,

and were in fact eventually destroyed at the end of World War II.

Around the same time, Klimt gave up his membership to Vienna’s premiere society of artists

(the Association of Austria Artists, or Kunstlerhaus) alongside a number of other

contemporary artists and designers. Klimt and his contemporaries were frustrated by what

they saw as the priority given to more conservative, traditional artistic styles when it came

to exhibition space. Along with others including architects Josef Hoffman and Otto Wagner,

and designer Koloman Moser, Klimt co-founded The Vienna Secession on 3 April 1897.

Although they refused an official manifesto, the group was designed to provide a space for

more radical young artists to exchange ideas and exhibit their pieces.

Whilst the Secession did eventually fracture and fall apart as a result of in-group fighting

and disagreement, with Klimt and others leaving in 1905, it was nonetheless a revolutionary

and reformative art movement that had been created in order to challenge pre-existing

academic traditions. It was during his time in the Secession that Klimt arguably created

some of his most famous pieces – including Fischblut (Blood of Fish).

Fischblut (Blood of Fish)

During the early years of the Secession, Klimt began to develop and play around with a

different style of space and representation, inspired by both Japanese wood block art and

the aesthetics of Greek vase painting. Both of these influences can be seen in the piece Fish

Blood.

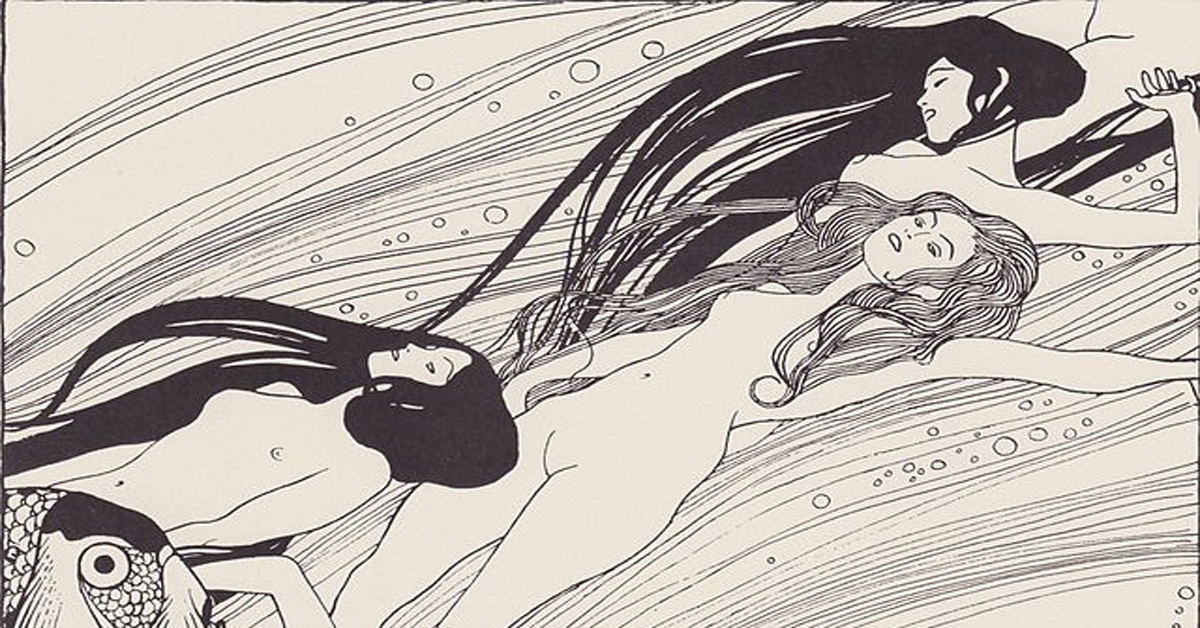

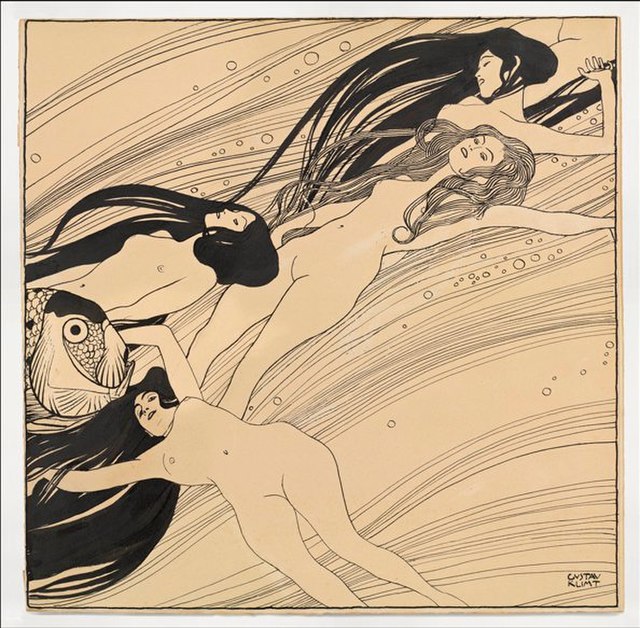

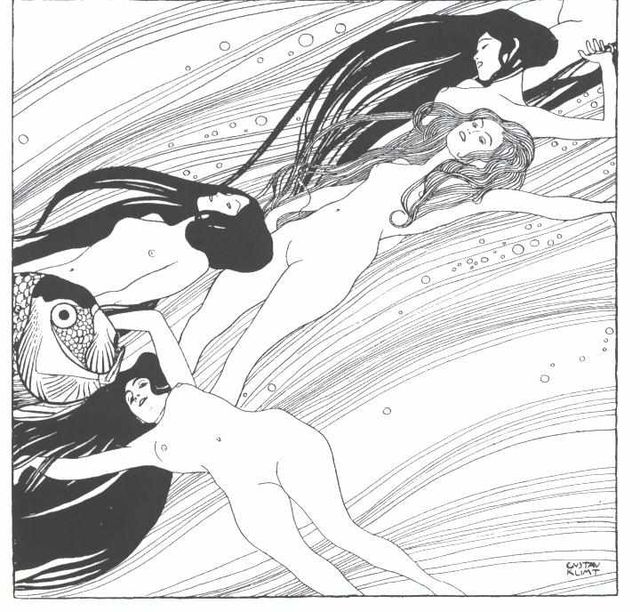

Fish Blood (Fischblut in Klimt’s native Austrian) was explicitly crafted for publication in the

Secessionists’ periodical Ver Sacrum (‘Sacred Spring’). It has been identified as Klimt’s most

important graphic work, and shows four naked female figures drawn from a combination of

brushwork and black ink, black chalk, and white highlights. The outline of the female bodies

is distinguished by way of firm, stark outlines, but whilst the piece departs from Realist

dimensionality, it nonetheless is a lively artwork with dimensionality created by its curves

and drawn detail.

Three of the four women’s bodies appear to drift towards the top right of the artwork, and

are accompanied by sweeping lines that reflect the women’s hair and, perhaps, seaweed, as

well as a number of aquatic bubbles. The most striking figure in Blood of Fish is the fish

head, which faces upwards, like the women’s bodies, and has been said to demonstrate the

connection of the human world of the women with the natural.

Fischblut (Blood of Fish) – style and aesthetics

Fish Blood (Blood of Fish) marked a stylistic departure for Klimt from a more classical,

conventional Realist aesthetic and artistic practice to a Modernist approach. The Art

Nouveau style that Fish Blood hints at continued throughout Klimt’s oeuvre, where he

continued to change his use of shape, figuration, symbol, and space, departing from the

three-dimensionality of Realism and embracing a cleaner, more contemporary approach to

the figure of the body.

The piece demonstrates Klimt’s focus on the female body, which would continue

throughout his work, eventually becoming a characteristic for which Klimt continues to be

famous.

The general aesthetic of Fish Blood (Blood of Fish) is luscious, and there’s an embrace of

pleasure, sensuality, and sexual freedom in the piece. The women’s free-flowing hair mimics

that of the clean, curved lines behind them, as they allow their bodies to recline and flow

freely in the water’s motion with a kind of ecstatic abandon.

It was this embrace of sensuality and pleasure – in particular female pleasure – that

characterised Klimt’s work moving forward. He continued to recoil from conservative

attitudes towards sexuality in a way that was genuinely radical at the time of his practice.

The focus on more radical themes and styles demonstrated by Fish Blood continued

throughout Klimt’s artistic practice, and, in fact, arguably had precedent in the ceiling

paintings that the University of Vienna commissioned from him and eventually rejected. The

painting Medicine, in particular, showed a floating female figure to the upper left of the oil

sketch, which is not dissimilar (though created in a more Realist style) to the floating female

figures of Fish Blood (Blood of Fish).

Interpretations of Fischblut (Blood of Fish)

The floating female bodies of Fish Blood occupy an undesignated time and space, and are

untethered in either, reflecting Klimt’s growing interest in the relationship between

humanity and nature, where humanity has no control over their fate in a wider universe.

This is conveyed by the incomplete figures in the piece – all of the women have their feet or

hands cut off, for example, and the top right figure is almost completely disjointed and

disembodied. Critics have argued that this further represents the metaphysics of an endless

life, as embodied by both the fish and female figures.

Fischblut (Blood of Fish) and other Klimt artworks

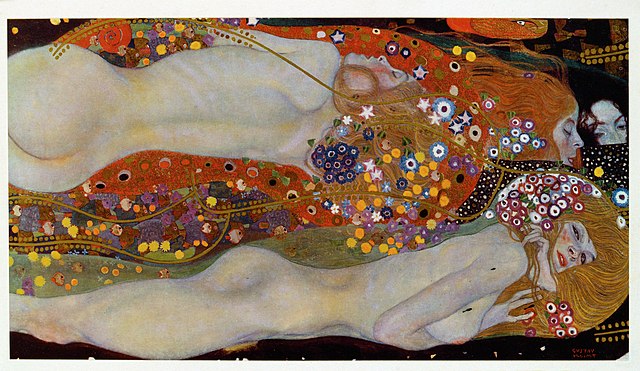

Fish Blood (Blood of Fish) can be seen as heralding future Klimt artworks, including Goldfish

(1901 – 02), Moving Water (1898), Nymphs (Silver Fish) (1899) and Water Serpents I (1904)

and Water Serpents II (1904 – 07). In each of these artworks, female bodies are displayed in

sensual, evocative positions, and possess a curving grace and ethereal embrace of their

pleasure and eroticism.

Goldfish developed the same Symbolism and Art Nouveau elements of Fish Blood, and

shows a similar use of the naked female body alongside aquatic figures and images,

including that of a goldfish head, much like in Fish Blood (Blood of Fish). Moving Water is

very similar to Fish Blood, in that it shows naked female figures enveloped by loose-flowing

hair, drifting through water. It has been suggested that Fish Blood was the inspiration for

Moving Water.

By virtue of the fact that Goldfish was initially named ‘To my critics’, it is clear that this piece

was created by Klimt in direct refusal of the very conservative attitudes that had resulted in

the refusal of his paintings by the University of Vienna. Klimt only changed the name of the

piece to Goldfish when he came to display it during a 1903 Secession exhibition, but the

press was nonetheless furious with the artwork for its explicitly erotic provocations.