Remembered for his role in co-founding the Vienna Secession in 1897 after splitting from

the city’s premiere society of artists, Gustav Klimt remains a significant figure for art history,

both for his own artwork and for his influence on the Austrian Expressionist painter Egon

Schiele.

Klimt’s ‘Golden Phase’ was without doubt the most successful artistic period of his life,

bringing him both critical repute and financial prosperity. Having used gold leaf in previous

pieces such as Judith I and Pallas Athene, Klimt began to integrate the precious metal into

his artistic practice on a more consistent basis during this period, which explaining why it’s

known as either the ‘Golden Phase’ or ‘Golden Period’ of Klimt’s work. It was during this

time that Klimt created The Kiss, which arguably remains his best-known artwork.

However, Klimt is also renowned and remembered for his celebration of the female form,

and his rejection of contemporary conservative attitudes towards sexuality and sensuality.

Having been trained in Realist techniques and aesthetics at the Vienna School of Arts and

Crafts, Klimt began to expand on and depart from more conventional artistic styles, taking

influence from international movements and artistic genres, such as Japanese wood block

art. Both of these interests are evidenced in Klimt’s artwork Silhouette I & II (1912).

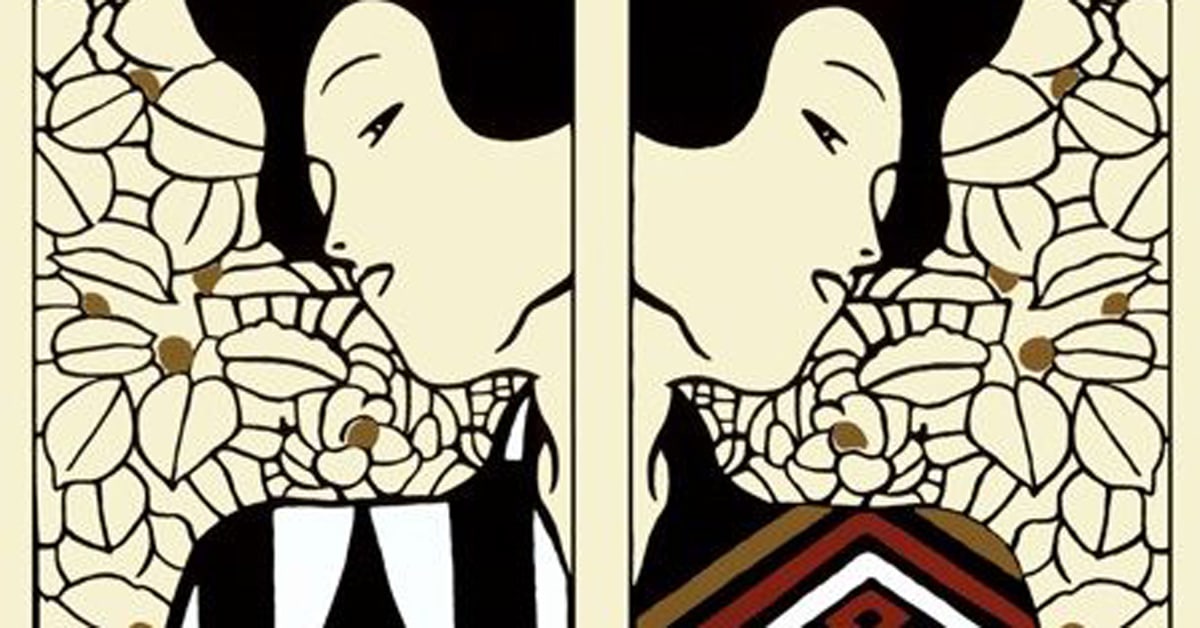

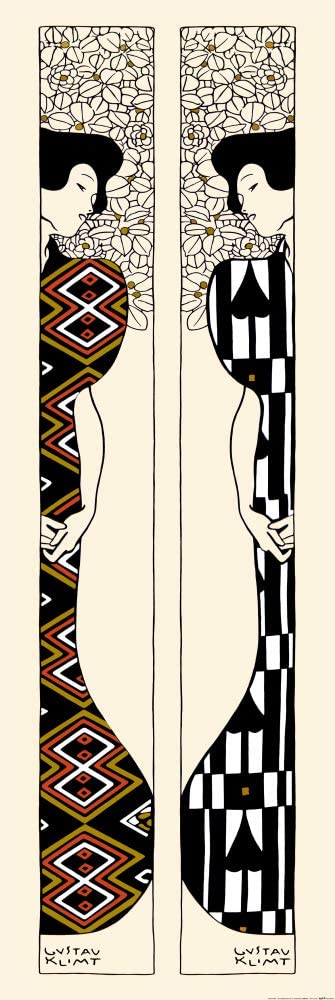

Silhouette I & II (1912)

Silhouette I & II was created in 1912, only six years before Klimt’s death in February 1918. It

shows the clear evolution of Klimt’s love of Japanese art and his celebration of the female

form, as well as the influence of other movements including Art Deco and Art Nouveau on

his work.

Silhouette I & II shows the figure of two women, who are identical in form and silhouette

but are facing away from each other in a mirror image. It is clear that whilst the women

appear identical – apart from the patterns of their dress – they are in fact not reflections of

the same person, as each figure can be seen clasping their two hands towards the center of

the image.

Both figures in Silhouette I & II wear a curving, fitted dress that swells out around the

shoulder and ankle. The dresses are decorated differently, with bold graphic designs that

reflect and resonate with the Art Deco influence of the drawing. The dress of the left-hand

silhouette is decorated with rectangles of differing sizes and the shape of spades such as can

be found in a card deck, and is colored in black and white with small golden squares. The

dress of the right-hand silhouette is black in color, with a repeating pattern of interlinked

diamonds shaded in gold, maroon, and white. Both silhouettes have the same hair, which is

jet black in color and resembles that seen in Japanese Ukiyo-e art and woodblock prints.

The background of Silhouette I & II is cream, and the silhouettes are drawn with confident,

clean graphic lines in black. Flowers spread across the top third of the artwork, and their

petals expand across the face of the piece. The design on the right exactly mirrors the design on the left. The work has a calligraphic quality and its bold graphic elements bring to mind another of Klimt’s artworks, Fischblut (Blood of Fish).

Styles and Artistic Genres That Inspired Silhouette I & II

Japanese Ukiyo-e Art

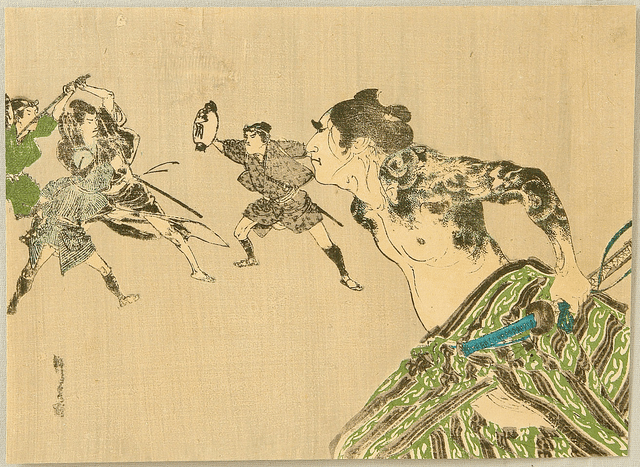

Translatable as ‘scenes’ or ‘pictures of the floating world’, Japanese ukiyo-e art clearly

influences Klimt’s Silhouette I & II. Popularized from the seventeenth to the nineteenth

century in Japan, ukiyo-e art began to influence Western painters from the late nineteenth

century, as heralded by the rise of Japonisme, a French term explicitly referencing the rise of

Japanese art in European cultural circles and artforms.

Ukiyo-e art emerged with the rise of the economically powerful chōnin class in the early

seventeenth century. Artisans and merchants of this class soon turned themselves towards

the pursuit of pleasure and entertainment as they became more financially stable and

successful, which brought about a burst of arts and culture, including ukiyo-e art.

The earliest ukiyo-e art was painting, and artists including Iwasa Matabei became proficient

in and recognized for this style and genre of art. This painting soon expanded into

woodblock prints and other artforms all blossoming under the umbrella of ukiyo-e, including

dance and drama. Schools like the Torii School, Katsukawa School, and Utagawa School

allowed artists to study and master this particular artform, which continued to flourish

towards a peak period in the late eighteenth century. Artists including Chōki, Utamaro and

Sharaku continued to be celebrated for their contribution to this Japanese artform.

Dominant and recognizable figures in ukiyo-e art include landscapes and images of birds and

flowers, as well as portraits of kabuki actors. Bijin-ga artwork was another popular genre of

the artform, which translates to ‘beautiful person picture’, where artists like Eisen, Shinsui,

and Kiyonaga would draw women celebrated for their beauty.

Although ukiyo-e art began to drop off in the late nineteenth century, it was one of the

major Japanese artforms to catch on in Europe. Impressionists like Degas and Monet were

inspired by the artform, as were others like Gauguin, van Gogh. Major artists associated

with the Art Nouveau movement, such as Toulouse-Lautrec, were similarly inspired. So, too,

was Klimt himself, and the influence of ukiyo-e art on Silhouette I & II is clear.

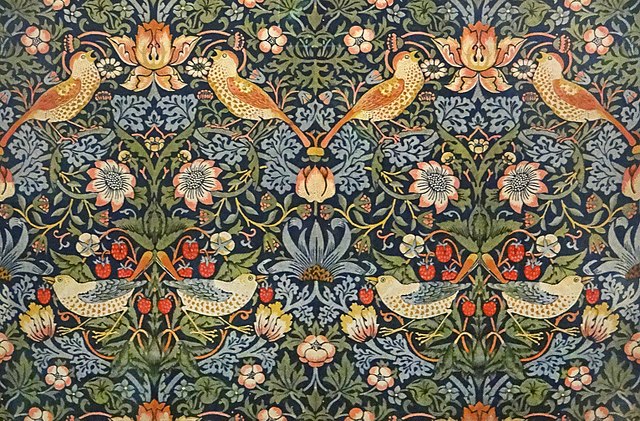

Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (or, ‘New Art’) grew from two nineteenth-century art movements – the

Aesthetic movement, which was a celebration of art for art’s sake, and the Arts and Crafts

movement, which privileged traditional techniques and craftsmanship and is typically

associated with the British artist William Morris. Art Nouveau also took influence from the

rise of Japonisme – particularly Ukiyo-e art – in Western markets.

As an ornamental style of art, the Art Nouveau style is recognizable by its use of long,

curved, organic lines that take influence and inspiration from the natural world. Art Nouveau took hold of different art and design practices, informing everything from jewelry

design and illustration to architecture. The influence of Art Nouveau on Klimt’s Silhouette I

& II can be seen in the artwork’s emphasis on strong, graphic lines and the themes of the

natural world that emerge in the piece.

Perhaps one of the best-known artists to practice Art Nouveau is the Catalan (Spanish)

architect and sculptor Antonio Gaudí, who embraced the movement’s celebration of natural

forms, texture, space and color to create buildings including the Sagrada Familia in

Barcelona. Other Art Nouveau artists included names like the French architect Hector

Guimard, the American glassmaker Louis Comfort Tiffany, and the American architect Louis

Henry Sullivan.

Art Nouveau was international in its appeal, but had particular draw for French artists,

designers and architects, where it was also variously called Style Jules Verne, Le Style Métro,

and Art fin de siècle.

Although Art Nouveau inspired a flurry of artwork and architecture that continues to be

appreciated to this day, it was broadly abandoned in the early twentieth century, when

Modernism became vogue. Art Nouveau was revitalized in the 1960s as a result of major

exhibitions held at institutions including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (1959)

and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (1966), and inspired artworks and graphics in

1960s Pop art.

Art Deco

As a design style from the 1920s and 1930s, Art Deco is recognizable for the geometric

design that characterize the style. Coined following the International Exhibition of Modern

Decorative and Industrial Arts, which was held in Paris in 1925, Art Deco soon took over Art

Nouveau in popularity, and its influence spread, informing the craftsmanship of everything

from furniture and textiles to cinema. Art Deco was informed by everything from the bold

geometrics forms of Cubism and the Vienna Secession which Klimt co-founded through to

Bauhaus and aesthetics stretching from India to Japan.

Clean, geometric shapes tend to typify Art Deco pieces, which was a movement designed to

celebrate the modernity of the machine, which explains the emphasis on clean, often-

repeated graphics, symmetry. The embrace of Art Deco eponymized the early twentieth

century’s embrace of glamour and sophistication, as well as wealth and a belief in the value

of technological progress. With the Great Depression and World War I, Art Deco fell out of

favor.

Amongst the best-known Art Deco artefacts include the Empire State Building and Chrysler

Building in New York City. In terms of Art Deco’s influence on Silhouette I & II, this can be

seen in the graphic, geometric prints that decorate the dresses of both silhouettes, as well

as the central focus on the female form.