Gustav Klimt continues to be remembered and celebrated for his art, as well as his role as a

co-founder of the Vienna Secession. Although Klimt has gained significant notoriety and

significance as an artist and figure in art history during the contemporary era, his work was

often dismissed as too erotic, sensual, and sexual at the time of its creation.

Klimt continues to be recognized for his use of the female body, and his boundary-breaking

– some would even say taboo – use of the naked or nude woman in his artwork. In fact, a

selection of Klimt’s graphite drawings are so explicit that they remain challenging to exhibit

today, which can make locating published examples of his erotic oeuvre a challenge.

The openness with which he engaged with themes that were considered abhorrent and

indecent at the time resulted in heavy criticism from the contemporary press. Rife rumors

about supposed love affairs with the subjects of his work also plagued Klimt: many of these

rumors remain unsubstantiated, but it is highly likely that his studio played host to less-

than-professional liaisons with nude female models that, unfortunately, was consistent with

the behavior of artists towards their models. This has prompted calls – and sometimes even

protests – for museums and galleries to clearly mention when male artists may have

mistreated their female models.

Klimt was a figure of great uproar and outrage, but his work unequivocally influenced artists

including Egon Schiele, whose own work expanded upon the use of the naked body first

embraced by Klimt.

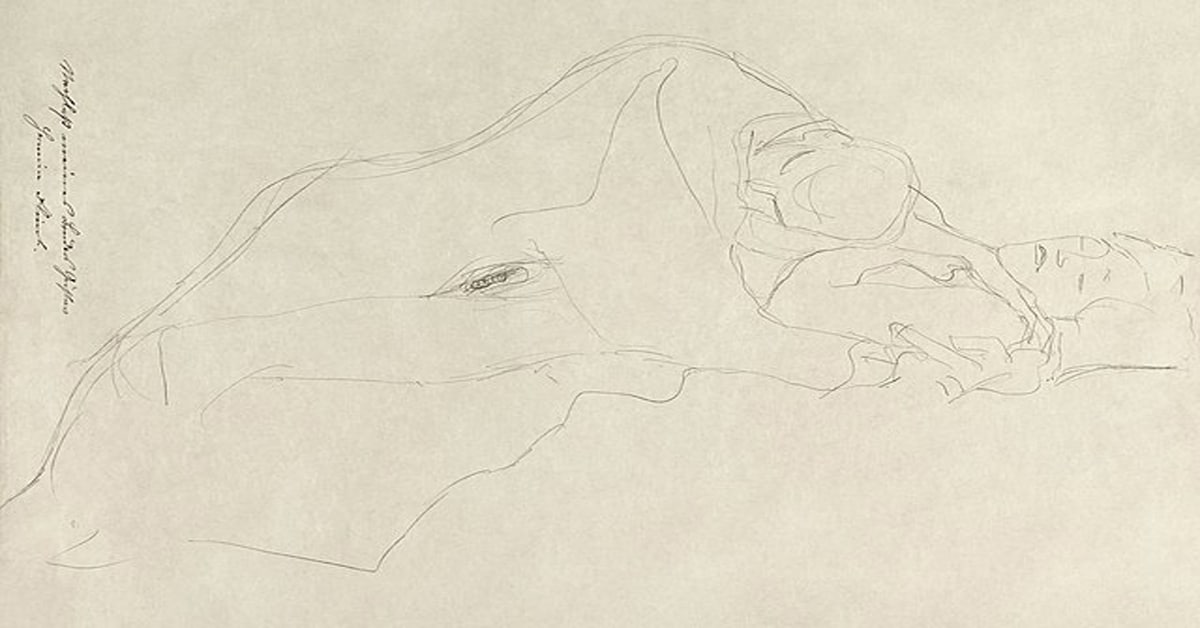

The Lovers

The Lovers, a piece created in 1913, is one of many graphite drawings by Klimt that

embraced the sexual and erotic. The Lovers shows a heterosexual couple (man and woman)

who engaged in lovemaking. The woman lays on her back, and, whilst her face, which is

directed towards us, demonstrates some degree of detail, the rest of her body is merely

suggested through Klimt’s spare use of delicate graphite lines. The man’s body has even less

detail: it hovers above the woman, and his head and facial features are faintly detailed.

Most central to The Lovers is the woman’s genitals. Compared to any other feature, these

are given the most detail by Klimt, and are also positioned centrally to The Lovers. The

drawing is explicitly sexual and taboo, and embraces the erotic, sensual, lustful nature of sex

and love, all of which were themes that Klimt leaned into as his career advanced, even and

in spite of contemporary criticism of his drawings as pornographic and repellent.

Klimt created over four thousand drawings (that are currently known), all of which were

dedicated to the female form. Many were undoubtedly sketched before commencing more

intensive work on a painting, as Klimt captured one of the many nude models that he had

pose for him.

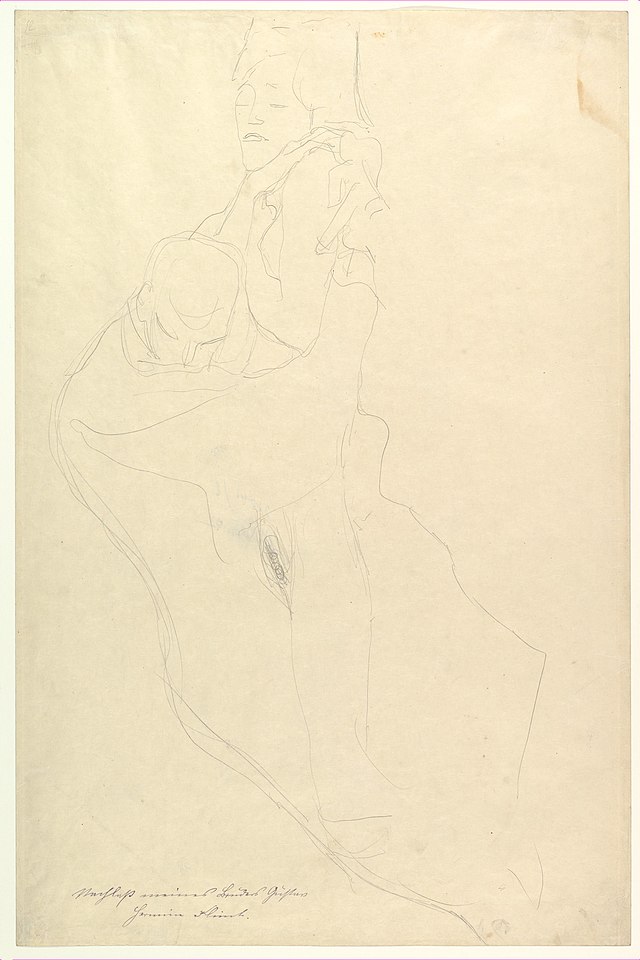

Images like The Lovers include Standing Nude (1906-07), Two Studies for a Crouching

Woman (1914-15), Nude Figure (1913-14), Reclining Nude with Drapery (1913), and

Reclining Nude with Leg Raised (1912 – 1913), although there are many others. Nude Figure,

Reclining Nude with Leg Raised and Reclining Nude with Drapery in particular, have distinct

kinship with The Lovers, but are arguably even more taboo, as both show a reclining woman

touching her own genitals. In total, there are around fifty drawings made by Klimt that show

women in the act of self-pleasure. The explicit, daring nature of these drawings is made

more apparent with recognition of contemporary laws around masturbation, which was

punishable by invasive, torturous surgical treatments.

Klimt’s Erotic Work – An Overview

The Lovers is dated 1913, meaning that Klimt created the piece after having abandoned his

membership to Vienna’s Association of Austria Artists, or Kunstlerhaus. Along with a

number of other artists and designers, Klimt renounced Vienna’s influential society of artists

in protest against what they perceived as extremely conservative values and practices.

Klimt already had cause to feel ostracized and criticized by a mainstream media who

deemed his work too explicit. In 1894, Klimt had been commissioned by the University of

Vienna to produce three ceiling paintings for the University’s Great Hall. Philosophy,

Medicine and Jurisprudence were criticized upon their reveal, however, for what was

perceived as their embrace of pornographic eroticism.

Philosophy depicted naked figures of all ages, but it was Medicine that arguably created the

most public outcry. Hygeia, the mythological daughter of the god of medicine, is shown

surrounded by nude figures, the most controversial of which is a floating nude female to the

upper left of the piece. What was perceived as the flaunting, thrusting pelvis of this figure

resulted in a number of politicians speaking out against the piece, which was critiqued for

what was perceived as its celebration of pornography.

The uproar caused by these three public commissions led Klimt to swear off public

commissions going forward, and may have further inspired him to lean into his celebration

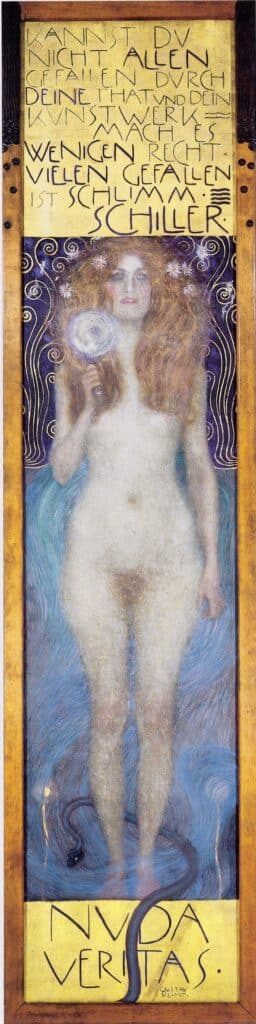

of taboo topics of sexuality, eroticism, and pleasure. In 1899, around five years after the

controversy over the pieces created for the University of Vienna, Klimt revealed Nudas

Veritas, a near life-sized depiction of a young naked woman. Atop the piece is a quotation

by Friedrich von Schiller, but it was the female figure who drew the most criticism,

particularly for its display of pubic hair around the genital area. Traditionally, female nudes

were depicted hairless, so this detail heralded a marked departure from convention by

Klimt. It was a practice that he carried forward into his erotic graphite drawings – in The

Lovers, for example, the woman’s genitals are not only central to the piece, but are also

drawn with pubic hair detail.

From December 1913 to January 1914, Klimt exhibited the largest number of his drawings

yet at the ‘International Schwarz-Weiß-Ausstellung’ (International Black and White

Exhibition). Many of these were his more erotic pieces, which resulted in heavy criticism

from critics. Consequently, Klimt was loathe to display his drawings publicly, so frustrated

was he at their tendency to produce uproar.

Klimt’s Own Lovers

Klimt sired sixteen illegitimate children during his lifetime. Alongside the criticism of his

work, rumors circulated about elicit relationships with his female models, although these

remain largely unsubstantiated. Given the long history of use and abuse of young women by

male artists, the topic remains controversial, and Klimt is certainly an ambiguous figure

within this discourse.

Klimt certainly had an ongoing relationship with Emilie Flöge, and it is often suggested that

his most famous artwork The Kiss is autobiographical, depicting both Klimt and Flöge. It has

been noted, however, that they never consummated their relationship sexually, and that it

was one of romantic and spiritual fulfilment. Flöge was an artist in her own right, and was as

committed as Klimt to abandoning the conservatism of Vienna.

Whether or not Klimt also had a relationship with Adele Bloch-Bauer remains a subject of

conversation in the artworld. Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I remains a celebrated

artwork with a storied history, and Adele was the only woman that Klimt painted more than

once. She has therefore been positioned by art historians as Klimt’s lover, although there is

no tangible evidence to prove this liaison definitely took place.

Certainly, The Lovers does not depict Klimt himself in a sexual encounter with any of the

women with whom he may have had trysts or affairs, but it remains a significant piece of

erotic artwork, and emblematic of wider themes in Klimt’s oeuvre.