The majority of Gustav Klimt’s artwork portrays the female body and its mystic nature. Even though there is no hard evidence, some researchers believe that he had some kind of connection to every woman he painted.

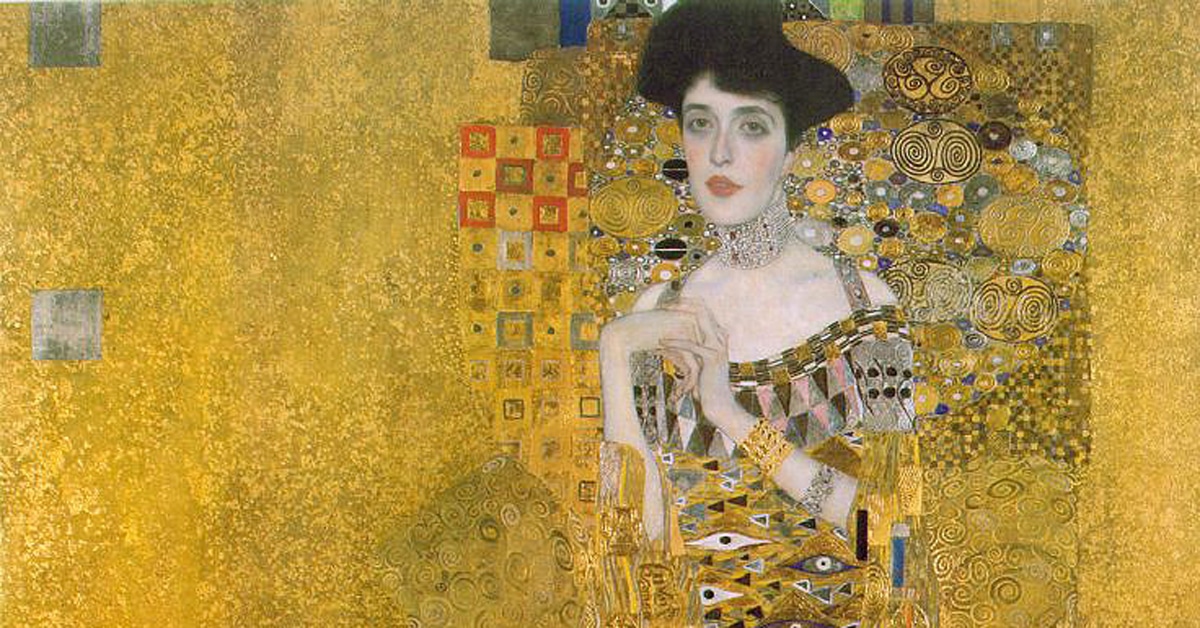

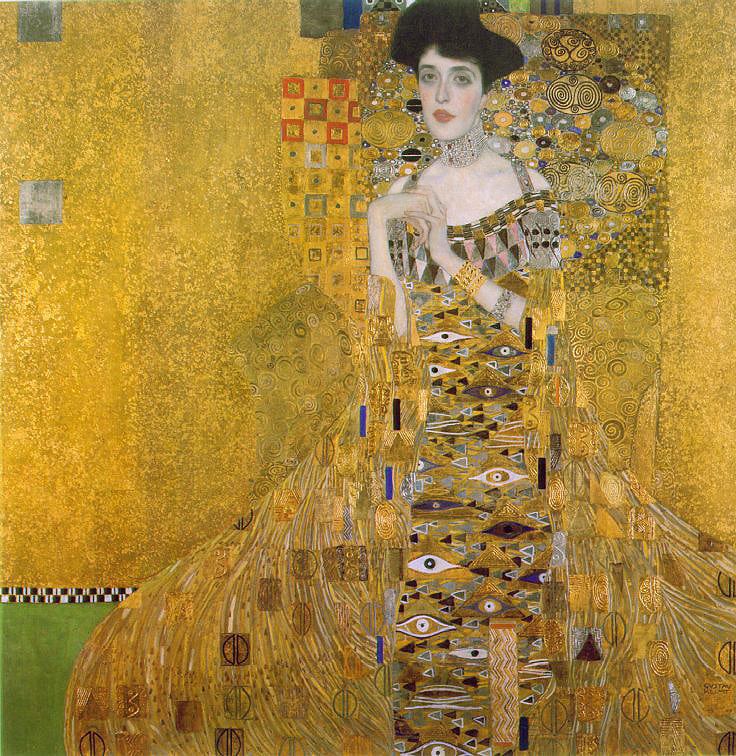

One of the most amazing and discussed pieces by Klimt is Adele Bloch-Bauer. This “golden” artwork has been subject to controversy. Therefore, you are not alone if you want to know more about it.

Wondering who the lady was in Adele Bloch-Bauer I? Or why did Klimt choose her to paint? Below, in this article, you will find all the answers.

Who Is The Lady In Adele Bloch-Bauer I?

Adele Bloch-Bauer was the subject of several of Klimt’s most well-known paintings. She was the art patron and hostess of the Viennese salon. The salon was often a place of gathering for prominent Viennese artists.

Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, the Jewish financier and sugar entrepreneur and the husband of Adele, commissioned the painting. Ferdinand purchased the picture for an astoundingly high sum and then went on to purchase further Klimt works for the family collection, which is one of the largest in Vienna. Gustav Mahler, Berta Zuckerkandl, Stefan Zweig, and Julius Tandler, among other well-known figures, visited her salon. Adele advocated socialism.

Adele is presented in Klimt’s two regal portraits, Adele Bloch-Bauer I and Adele Bloch-Bauer II. Yet, it is believed that she is the person in the artwork of Judith. All three of these works attest to the historical significance of Jewish sponsorship during Vienna’s Golden Age of late 19th-century art.

Life Of Adele Bloch-Bauer

Moritz Bauer (1840-1905), a banker, and Jeannette Bauer née Honig (1844–1922) were Adele’s parents. They had seven children, and Adele was the youngest one. She was born on 1881, August 9. Her father served as both the head of the Orient railway business and the general director of the powerful Viennese Bank organization.

The early passing of her beloved elder brother Karl left a significant mark on her life. She was only 16 years old when this happened. She probably drifted away from religion as a result of the trauma of his death.

She married Ferdinand Bloch (1864–1955), a sugar industrialist who was seventeen years older, on December 19, 1899. The marriage happened after she was denied the chance to attend school and felt unfulfilled in her parents’ home.

Her marriage came after her sister Therese wed Gustav Bloch, a doctor of law, who was Ferdinand’s brother. There were no living offspring for Adele and Ferdinand. She gave birth to a stillborn girl in February 1903 and a son named Fritz in early October 1904, who passed away just one day after his birth.

These traumatic experiences may have impacted Klimt’s decision to immortalize Bloch-Bauer in his two (possibly three) magnificent paintings of her, including Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Art historians have only recently begun to take these events into account.

Bloch-Bauer could have discovered her role models in love literature. She took it upon herself to study classical literature in German, French, and English. She appeared to be in pain because she was delicate, prone to sickness, and suffered.

Bloch-Bauer passed away suddenly from meningitis in Vienna on January 24, 1925. The “Klimt Hall” was converted into a chamber in her honor when she passed away. She left her money to several charities in her will, including The Society of Children’s Friends.

She gave her collection to the Public and Workers’ Library in Vienna. She also asked that, following her husband’s passing, the works by Klimt be given to the Austrian Gallery. The Austrian State Gallery Association, founded in 1912, had Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer as a founding member and supporter.

Creating Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer commissioned Gustav Klimt to paint his wife’s portrait in the summer of 1903 to give it to her parents for their wedding anniversary in October. Only early in 1907 was the portrait made available for public viewing.

In the picture of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, a lady is seated straight on a throne made of gold. She seems to be the grand dame of today. Her gorgeous golden gown is complemented by the starry golden sky background, which also hints at a potentially close relationship between the artist and his model. Additionally, the sensual relationship is expressed by symbols such as triangles, eggs, and eyeballs.

The use of abstracted eggs as fertility symbols in Adele Bloch-Bauer I painting may appear as a cruel allusion to Bloch-stillbirth Bauer’s in 1903, which took place before Klimt started the portrait’s preparatory drawings. Or it may have been an attempt to symbolically “impregnate” Bloch-Bauer in an attempt to make up for her stillbirth and the passing of her infant son in 1904. After her terrible loss, he kept working on the painting. Klimt made an effort to highlight Adele’s distinctive hand motions as an integral component of her persona. The fists are tightly clenched together.

It is believed that the gesture was inspired by Georg Minne’s emotional and romantic artwork “The Outcasts,” which was created in 1898. It may have been because the artist was trying to conceal a deformation of her right hand’s middle finger, about which she was self-conscious. Both Klimt and Adele were fond of Georg Minne.

Adele Bloch-Bauer I had the appearance of being a well-balanced amalgam of romantic personae. On the one hand, ill and frail, and on the other, a self-conscious and proud salon woman. Her slender face was beautiful and smart, but also haughty and condescending.

Other Portraits Of Adele Bloch-Bauer

Klimt’s earlier 1901 depiction of “Judith” as a femme fatale, in which Adele is identified by facial traits and a flashy neckband, similar to the neckband in her later picture, provides another example of the imaginative envisioning of his connection with Bloch-Bauer.

A modern critic recognized a Jewish lady from today as the inspiration for “Judith.” The neckband “beheads” Bloch-Bauer as well as Judith. In this way, Klimt highlights the expectant expression of the mythical and real lady, Judith’s daring and sexual expression, and Bloch-thoughtful Bauer’s sentiments.

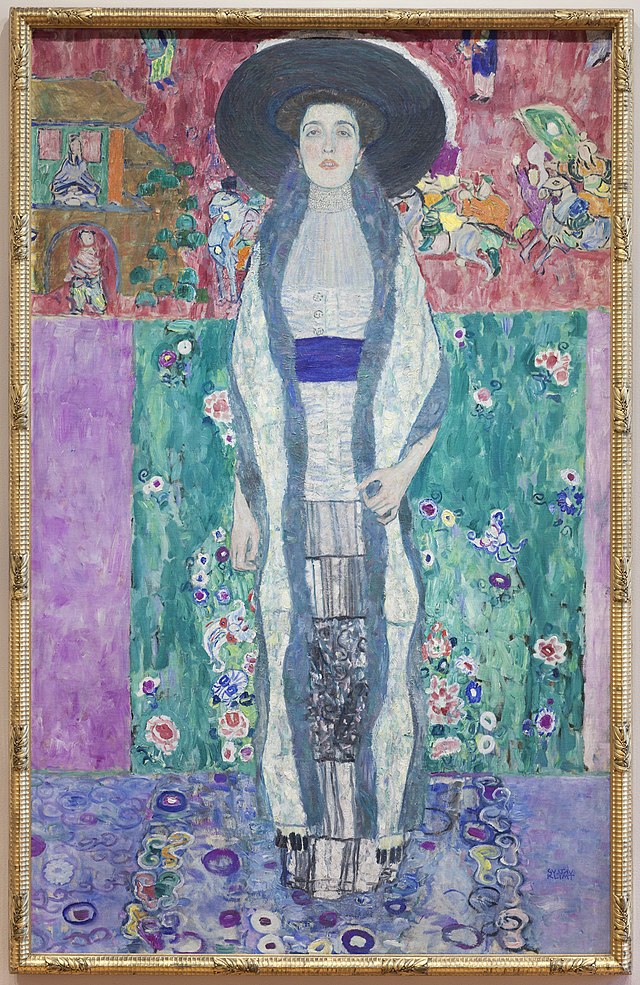

In a second image, Adele Bloch-Bauer II, from 1912, Adele is posed standing up and sporting a stylish outfit. A scene from the Far East featuring galloping horse riders returning to their villages can be seen behind her in the top portion of the vibrant background. The far eastern setting might be a reference to the Jewish woman sitter’s cultural affiliation with the Oriental or “exotic” world and a confirmation of her status as the “other.”

Relationship Between Adele And Klimt

Although rumors of a relationship between Bloch-Bauer and Klimt were never proven, it is reasonable to believe that the artist’s romantic allusions to his subject are what drive her stunning image. The Wide and Husband Bloch-Bauers also acquired four landscapes and other Klimt works, in addition to the two portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer I.

They both took great pride in their art collection, which included works by well-known Austrian painters such as Emil Jakob Schindler, Rudolf von Alt, and Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, as well as a priceless assortment of Viennese classical porcelain.

Adele built a shrine to Klimt in her rooms in 1919 after the couple relocated to their new palatial castle in Vienna across from the Academy of Fine Arts. The room’s walls were covered with his paintings, which included Adele Bloch-Bauer I, and a side table had a picture of him.

Legal Battles Over Adele Bloch-Bauer I Portrait

Ferdinand escaped Vienna in 1938 when Nazi Germany annexed Austria. He left the paintings behind, and the Nazis confiscated them along with a large portion of his other belongings under the pretense that Ferdinand had avoided paying 1.4 million Reichsmarks in taxes.

Nazi officials like Adolf Hitler and others claimed items from the Bloch-Bauer collection at very low rates. To completely omit all mention of its Jewish subject, the picture of Adele was eventually moved to the Galerie Belvedere and given the new title “Lady in Gold” or “Woman in Gold“.

Ferdinand Bloch-Last Bauer’s will, which was written in 1945, bequeathed his whole estate to his nephew and two nieces. He didn’t exactly name the artworks since he believed they were permanently lost.

The Austrian government adopted the Art Restitution Act in 1998, many years after the war and Bloch-passing, to determine which works of art should have been restored to their original owners. Marie Altmann requested the return of six Klimt paintings through a claim made to the restitution committee. According to the committee, Adele willfully gave the museum legal rights to the artworks.

Five of the six paintings, including the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, were restored to Altmann after a protracted legal dispute between the Austrian government and Altmann. She sold it to billionaire and art collector Ronald Lauder, who had it shown at New York’s Neue Gallery.

Final Thoughts

Adele Bloch-Bauer I is among Gustav Klimt’s most famous artworks. He created it between the years 1903 and 1907, and it took him four years to finalize. This Klimt artwork is one of the few from his Golden Period, when he created incredibly ornate pieces that resembled jewelry boxes. Klimt worked on the painting for years and made over 200 preliminary drawings.

A well-known 2015 movie called “Woman in Gold” was based on the restitution lawsuits of the relatives of Adele’s husband, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, notably their demand to return her Klimt pictures.